In August last year, Parliament removed Articles 370 and 35A of the Constitution from the statute book, effectively emasculating the special status of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). It followed this up by carving out two Union Territories of J&K and Ladakh from the State of J&K. The asymmetric character of the Indian federal structure notwithstanding, the manner in which the changes were effected caused a great deal of dissonance. Criticism was, nevertheless, muted given assurances that the step would ensure a more closely integrated Indian Union. Pakistan, predictably, criticised the

step, while China raised its voice observing that the bifurcation of J&K and the voiding of Article 370 should not be seen as solely India’s internal matter.

Use of ‘shock and awe’

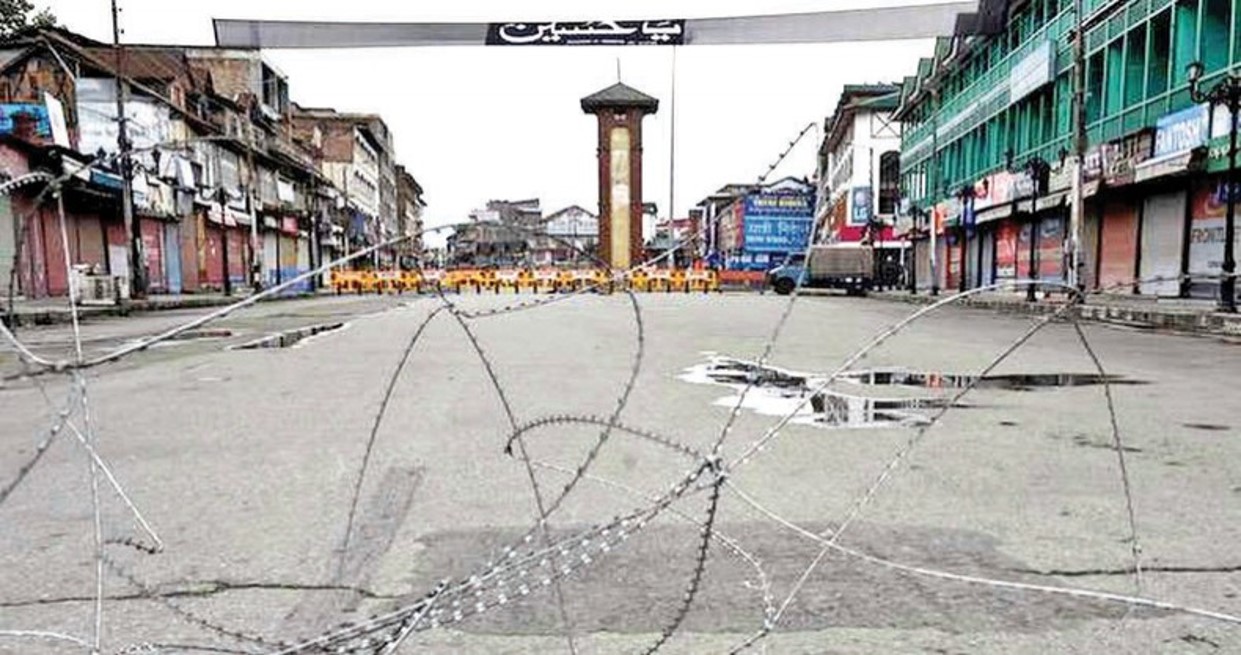

The August 2019 move confirmed the Centre’s willingness to resort to ‘shock and awe’ tactics to achieve pre-determined objectives, irrespective of whether the end results were achievable or not. The move on J&K was unexpected, the closest parallel possibly being demonetisation. In both instances, the decisions were taken in utmost secrecy, leaving no scope for discussion, debate or retreat. The rashness of the determination to ‘cross the Rubicon’, and erase the notion of a separate ‘Kashmiri identity’, was not dissimilar (though in a totally different context) to the use of air power to hit targets inside Pakistan (in February 2019).

Ruling party spokesmen went to considerable lengths to argue that the August 2019 decision was aimed at ending an anomaly that had existed for long, and had impeded Kashmir’s peace and progress. To sugar-coat the decision, prospects were held out of vastly enlarged economic and job opportunities, reduction in levels of terrorist violence, closer integration with the rest of India, etc. At the time, much of India seemed to accept this line of argument, though there were quite a few who objected to the stealth and secrecy that preceded the announcement of abrogation of two key Articles of the Indian Constitution, and the stringent security measures that were enforced across J&K, immediately prior to and subsequently.

Unrealised goals, concerns

The laundry list of achievements and missed targets post-August 2019, however, suggest that the intended objectives of bringing Kashmir into the national mainstream, reducing levels of violence within the Union Territory, and expansion of jobs and economic opportunities, are still to happen. Levels of violence continue to remain high, broadly approximating to what existed in earlier periods. The only silver lining has been the elimination of some top leaders of terrorist outfits, such as the Hizbul Mujahideen.

The incarceration of several senior political leaders for several months under various provisions of the law, including the Jammu and Kashmir Public Safety Act, has, meanwhile, undermined faith in the Centre’s commitment to an early return to orderly political discourse. Senior leaders like former Chief Minister, Mehbooba Mufti, still remain in custody. Prominent National Conference leaders, Farooq Abdullah and Omar Abdullah, have been released from custody, but continue to face restrictions, with regard to any kind of political activity. Peoples Conference chief Sajad Lone was released after spending almost a year in preventive detention. The widespread concern about human rights and human rights violations in Kashmir, hence, appears justified. As former Supreme Court of India judge, Justice Madan Lokur, observed in a recent newspaper article, that even a form of house arrest is a matter of grave human rights concern.

Among other major concerns has been the difficulty faced by the populace in accessing information, following the snapping of high speed Internet connections. Students, in particular, have faced serious problems on account of the lack of access to high speed Internet. Another has been the State government’s announcement (in May this year), to notify the J&K Grant of Domicile Certificate Procedure Rules, 2020 and set a fast track process in motion. The domicile certificate issue has become a ‘ticking time-bomb’, with some political parties declaring that it could “change the

demography of the erstwhile State of J&K”. The latest notification allows non-locals to apply for domicile certificates, thus potentially opening the floodgates for ‘outsiders’ to settle in the State, acquire property, and also apply for jobs in an already scarce job market.

Even Jammu which had less to lose on account of the changes effected in August last year, has its own list of concerns, mainly relating to the likely influx of outsiders into the State following the removal of restrictions. The inability of local businesses to compete with goods from outside is another of their special concerns. Together with the higher cost of manufacture in J&K, as also the need to import raw material from elsewhere, concerns abound about their ability to compete with ‘outsiders’.

The complexity of Kashmir

India has had problems with Kashmir ever since 1947. The reasons are too well known to merit repetition. Successive governments in Delhi and Srinagar have wrestled with the problem. Kashmir has also figured prominently in at least four India-Pakistan conflicts, and the Kashmir issue has been a constant irritant in India-Pakistan relations. Anyone who deigns to read the debates in the United Nations on Kashmir during the 1950s and 1960s, and even subsequently, will understand the complexity of the Kashmir problem. Every government in Delhi has dealt with Kashmir during their tenure in office, and there has been no lack of trying on their part to solve the issue.

Many options on how to deal with the problem have been previously explored. In the past, the security problem had attracted the attention of renowned international experts, with experience in dealing with insurrections, sub-nation tensions, terrorism, and various other facets of organised and unorganised violence. During the final decades of the 20th Century, many saw a parallel between the situation in Kashmir and that prevailing in Northern Ireland. There was also a steady exchange of ideas and concepts with a view to finding a solution. A major difference between Northern Ireland and Kashmir, however, was that unlike in the case of the former, Kashmir had two hostile neighbours, one of whom was intent on instigating violence and providing a suitable ‘rear’ for terrorist elements.

Long shadow of world events

It is a moot point whether a long-standing problem of this nature can be solved merely by rejecting notions of a ‘separate Kashmiri identity’, disowning all talk of Kashmiri ‘insaniyat’ and ‘jamhooriyat’, and making Kashmiris pay for their past mistakes. An ingrained belief that the solution lay in squeezing Kashmir’s politics into the ‘straitjacket’ of national politics, shorn of all past beliefs and practices, could prove to be highly misplaced. It would amount to proposing a simplistic solution for a complex problem.

The Kashmir problem cannot again be detached from the extant situation prevailing in parts of the world, where many existing systems are undergoing changes. This crucial aspect of current history cannot be voided.

Across the globe, for instance, radical Islamist ideas appear to be gaining ground, and the impact is being felt on youth in our region as well. No longer can it be solely attributed to the fallout of the Afghan Jihad of the 1980s, for there are other forces such as the Islamic State in existence today, that are a force to reckon with. This must be recognised even as claims are being made that home-grown militancy in J&K has been extinguished. There are sizeable pockets of radical Islamist influence present in Kashmir today. One index is the existence of the so-called ‘unattached militant’.

All such elements are driven by the power of an idea, and cannot be suppressed through sheer force. These are among the fundamental issues that need resolution in Kashmir. Have debate, introspection Current policy makers should not assume that it is a failure of imagination, or of policy making, that prevented past leaders from understanding and finding a solution for the Kashmir problem. It would be wise for leaders in Delhi to be careful not to view immediate dividends as representing a new dawn, and should instead pause to try and ascertain what lies beyond the horizon.

Restoring normalcy should be an urgent priority even if many of the senior political leaders in Kashmir belonging to the National Conference, the People’s Democratic Party, or PDP, the J&K Congress, and the J&K Peoples’ Conference appear highly critical of the Centre’s policies. An intense debate must start as to where we go from here. Introspection after the initial one year has become essential. ‘Strong arm populism’ has its limits. A moment arises in the course of any struggle when it becomes necessary to undertake value-based judgements. In Kashmir, the moment is now. We cannot afford any more ‘evolutionary adaptations to an already dangerous social and complex environment’.