Gilgit-Baltistan (GB), formerly known as the Northern Areas, is a sparsely-populated mountainous region in the north of Pakistan, landlocked between India, China and Afghanistan. Since a treaty signed in 1846 between the British and the ruler of the Dogra dynasty, Gulab Singh, GB had been a part of the State of Jammu and Kashmir. In the present context and from an international perspective, however, it is disputed territory and has been under Pak control since the partition of British India in 1947. The 1949 secret Karachi Agreement gave the Pak’s Government direct control over the region and, despite the region relying entirely on Islamabad for its economic needs, GB has been neglected by Pakistan’s constitution to date. Pakistan’s Prime Minister, Imran Khan, has declared that he wants to elevate Gilgit-Baltistan’s legal status to that a province, which move would make the region fully autonomous and represented in the country’s parliament.

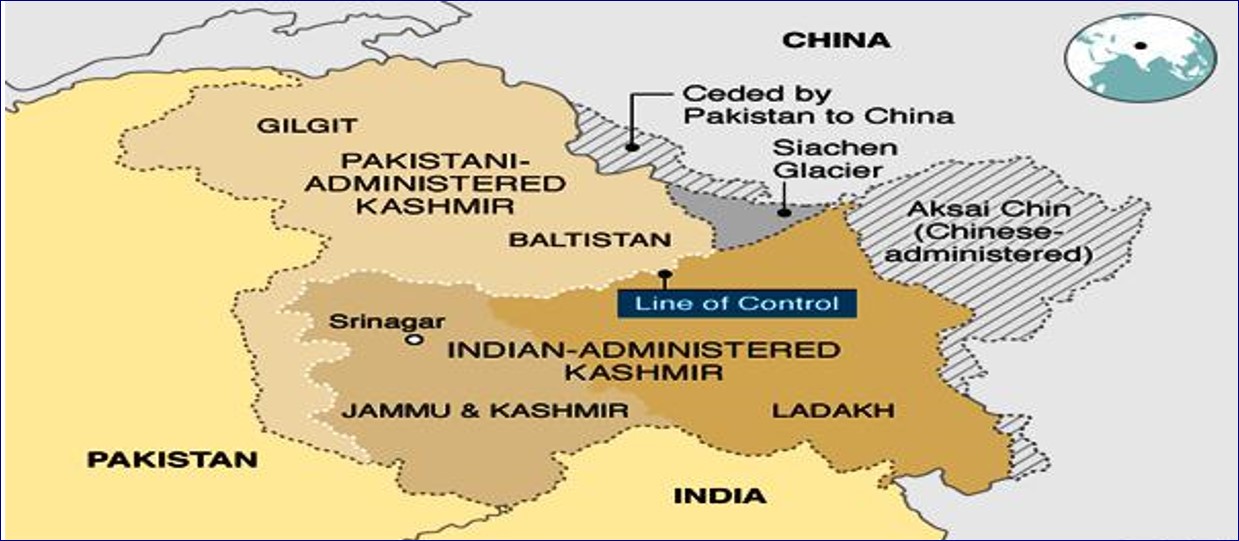

India has denounced Pakistan’s decision, claiming that GB is ‘illegally and forcibly’ occupied by Islamabad and that the latter has no locus standi to alter its status. India’s Ministry of External Affairs reiterated that ‘the Union Territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh, including the area of so-called “Gilgit-Baltistan”, are an integral part of India by virtue of the legal, complete and irrevocable accession of Jammu and Kashmir to the Union of India in 1947’. India maintains its claim to the entire territory of Jammu and Kashmir that includes Pakistan-administered Azad (Free) Jammu and Kashmir (AJK), the Kashmir Valley, Ladakh, Aksai Chin and Gilgit-Baltistan.

China’s ambitious China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) that connects Gwadar Port in Pak’s Balochistan with its Xinjiang province is a massive civil infrastructure project in which Beijing has invested around US$62 billion ($85 billion). The initiative is believed to engender huge strategic benefits to Beijing by mitigating its energy security dilemma in the Indian Ocean, consolidating its position in Indo-Pacific geopolitics and securing its energy supplies from the Middle East. Beijing’s substantial investments are, of course, a major driver of Islamabad’s actions in GB; as an anonymous senior foreign ministry official in Pakistan said, ‘China does not want to risk its investment in a disputed territory and has prompted Islamabad to fix the legal status of the GB.’ Pak’s total control over the restive region of GB is imperative for the viability of CPEC.

The local population of GB has resented the Pakistani federal government’s administration for the last seven decades and have complained of political partisanship. Earlier this year, the Supreme Court of Pakistan allowed the government to conduct general elections in GB and raise its constitutional status to that of a “provisional province”. Although Pakistan has defended its decision, saying that ‘Administrative, political and economic reforms are a longstanding demand of the people of Gilgit-Baltistan’, the whole exercise appears to be more of a response to the abrogation last year by New Delhi of Article 370 of the Indian constitution in Kashmir.

The ensuing long-term implications of Islamabad’s decision will be far more extraordinary than is envisaged currently because both China and India are major stakeholders in the disputed territory.

Analysis

The nineteenth-century struggle for supremacy between the British and Russian Empires in Central Asia, commonly referred as the “Great Game”, recognised the strategic value of the Gilgit-Baltistan region. Over the decades, the vested interests of Britain, Russia and China saw them focus increasingly on GB, the region’s importance being highlighted by British Viceroy Lord Curzon, when he observed, ‘It is one of the northern gates of India, through which the enemy must advance, if he advances at all.’ At the time, to prevent a Russian invasion from Central Asia and to secure the northern borders of the British Indian Empire, the British leased GB for 60 years from the princely ruler of the State of Jammu and Kashmir, Maharaja Hari Singh. Two weeks before the British Empire relinquished power in India in August 1947, it prematurely terminated the lease and handed the region’s direct control back to Hari Singh. A rebellion by the Gilgit Scouts made the Maharaja apprehensive, who then acceded to India on 26 October 1947 and sought military assistance against the rebels. On 1 November 1947, after Hari Singh’s Governor in Gilgit, Ghansara Singh, surrendered, the rebels declared the region as the independent state of the “Islamic Republic of Gilgit” and, after a mere 15 days of independence, acceded unconditionally to Pakistan. Since then, GB has remained in a state of limbo: constitutionally, neither Pakistani territory, nor part of Kashmir; fully controlled, however, by the Ministry of Kashmir Affairs in Islamabad.

The Situation in Gilgit-Baltistan

Pakistan has since maintained its control over GB, ignoring the UN resolution to completely vacate the region for a plebiscite to happen and has suppressed the persistent struggle by the locals for fundamental human rights. Pakistan declared GB a disputed territory and, to strengthen its stance on the Kashmir issue at the United Nations, continued to deny GB constitutional recognition, which, as a result, kept the region largely poor and underdeveloped. Former Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, of the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), initiated reforms in 1973, but it was only around 2009 that debates and discussions began to formulate the integration of GB into Pakistan. In 2015, during Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s tenure, GB’s assembly demanded the status of “provisional province” for the region until the Kashmir conflict was resolved in accordance with UN resolutions.

The international community is aware of the Kashmir issue. Little is known, however, about the sectarian policies exercised by Pakistan in Gilgit-Baltistan, where fundamental human rights have been denied since 1947.

A sense of neglect, exploitation and discrimination prevails among the local population; their semi-autonomous region was not included in the CPEC negotiations and an ‘atmosphere of secrecy and confusion’ encircles the whole project. Also, the peculiar regional asymmetries in the CPEC budgetary allocations that favour Punjab Province exacerbate the destitution of Gilgit-Baltistan’s people. There are concerns that the CPEC will lead to heavy securitisation of the area due to the fear of Islamist terrorist attacks in retaliation for China’s treatment of its Uighur Muslim minority in its western Xinjiang province. A large Shia Muslim community in GB blames mainly Sunni-populated Pakistan for systematic partiality, as the literacy rate in GB is just 14 per cent, far below the average rate of 31 per cent in Pakistan, with the literacy rate for women a mere 3.5 per cent. Sectarian violence is not uncommon; in 2012, the Sunni Jundullah group massacred several members of the region’s Shia Muslims.

The Real Winner: Gilgit-Baltistan or China?

Since the CPEC was initiated, Beijing has actively pressured Islamabad to formulate a permanent solution to the uncertain constitutional status of GB in order to neutralise any repercussions that may jeopardise its investments or hinder the development process. It aimed to eliminate any roadblocks such as local protests in acquiring land, essential for the success of the ambitious project. Lately, the Minister for Kashmir Affairs, Ali Amin Gandapur, announced that the Chinese-financed Moqpondass Special Economic Zone, which required 250 acres of land officially and 500 acres unofficially, will be expedited. The benefits for China are incomparable to the initial costs, with Gwadar Port, capable of facilitating trade from the Persian Gulf and Africa to western and northern China, reducing the distance by almost 12,500 kilometres and cutting transportation and other costs by billions of dollars. Upon completion of the pipeline projects, the time taken for China to import oil will be slashed to just two days from the current thirty, while minimising the anxiety in Beijing about vulnerable maritime routes. Pakistan’s Foreign Minister, Shah Mehmood Qureshi, in a recent meeting with newly-appointed Chinese Ambassador to Pakistan, Nong Rong, urged China to speed up CPEC projects at the strategically vital Gwadar Port and expressed his gratitude for Beijing’s steadfast support on the Jammu and Kashmir dispute, including at the United Nations.

The famous proverb, “all that glitters is not gold”, applies, however, to the emerging economic and loan-repayment crisis in cash-strapped Pakistan, which recently requested China to waive the US$30 billion ($41.2 billion) owed due to power supply projects, in order to negotiate its severe financial difficulties. Moreover, a committee appointed by Mr Khan to audit the high costs of power to Pakistani consumers underscored the corruption involving Chinese private power companies. The committee’s report noted that:

… excess set-up costs of Rs32.46 billion ($281 million) was allowed to the two coal-based [Chinese] plants due to misrepresentation by sponsors regarding [deductions for] the “Interest During Construction” (IDC) as well as non-consideration of earlier completion of plants.

These corrupt practices will eventually place added financial pressure on Pakistan’s government, which may find it difficult to service its loans and, arguably more importantly, on the Pakistani people.

The Sino-Pak relationship that Pakistan vociferously declares is more of a strategic game for China, subtly continues to exploit the Indo-Pak enmity to gain regional strategic advantages. However, debt-ridden Pakistan refuses to acknowledge the loss of its self-esteem that is, of course, an outcome of over-dependence on Chinese funds to keep its economy afloat. It is, nevertheless, digging itself a deeper hole by constantly accepting the so-called “gifts from China” that are worth billions of dollars and is on the verge of risking its national identity, much like Sri Lanka and the Maldives. AJK President Sardar Masood Khan lately said that China does not believe in war, but India’s extremist leaders constantly seek to push the region towards war. He asserted that ‘every attempt to sabotage the CPEC would be foiled’ and that Indian actions in the [Kashmir] Valley may culminate in a war. India and Pakistan, which were once one nation, fought against British rule together and have remarkable cultural similarities, have often attempted to resolve these issues bilaterally. China’s self-interest and gradual intervention, however, have only widened the crack in a strained relationship.

Despite reassurances, the people of Gilgit-Baltistan may continue to strive for their rightful share of CPEC benefits while Islamabad ignores them.

Geopolitical Implications

Despite Pakistan’s protestations to the contrary, it is quite apparent that the abrupt decision to amend GB’s status has been made because of India’s August 2019 constitutional change in the Kashmir Valley, which permitted Indian citizens to buy land and property there and to integrate with the local population. Islamabad called India’s actions a ‘clear violation of UN Security Council resolutions, bilateral agreements between Pakistan and India, and international law’. Mr Khan has accused Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party of abusing its majority in parliament to change the demographic structure of the disputed territory and making Kashmiris a minority in their own land, amounting to a ‘war crime’. India’s unilateral move, which it calls an internal matter, put Pakistan in an embarrassing situation when it failed to gather much international support for its stance on Kashmir. From Pakistan’s perspective, taking over GB would be an appropriate response and, indeed, appears well-timed.

In response to India’s Defence Minister Rajnath Singh’s statement that, ‘Pakistan has illegally occupied Gilgit-Baltistan’, Pakistan commented, ‘Administrative, political and economic reforms are a longstanding demand of the people of Gilgit-Baltistan. The envisaged provisional reforms reflect the aspirations of the indigenous populace of Gilgit-Baltistan’. Observers have, however, asked why, if Pakistan’s decision was made to address the prosperity of the people of GB, it has taken 70 years when Pakistan always had other means to address the underdevelopment and inequality issues.

Pakistan’s former envoy to India, Abdul Basit tweeted:

My advice to Islamabad – think hard on GB. A step taken in reaction to what India did to IOK [Indian-Occupied Kashmir] will engender avoidable controversies. Don’t stir up a hornet’s nest and weaken Pakistan’s principled position on [this] dispute….

Domestically, there is a mixed response to the planned amendment, with a part of the population ranged against the decision and hoping to resolve the issue in accordance with UN norms.

Pakistan may have implicitly acknowledged that Kashmir is a lost cause and that it may be in its best interests to secure Gilgit-Baltistan now before it is too late. India, on the other hand, admits the strategic value of GB, but understands that it is not worth going to war over. The issue is as contentious as it is important, but offers minimal room for India to manoeuvre around. China already has a strong foothold in GB and will possibly continue to tighten its grip in Pakistan in order to fuel its own economic growth and, at the same time, keep in check a growing India. It is unfortunate that in this broad context of winning and losing, the interests of the people of Gilgit-Baltistan do not occupy much space.

Courtesy: Talib Islam