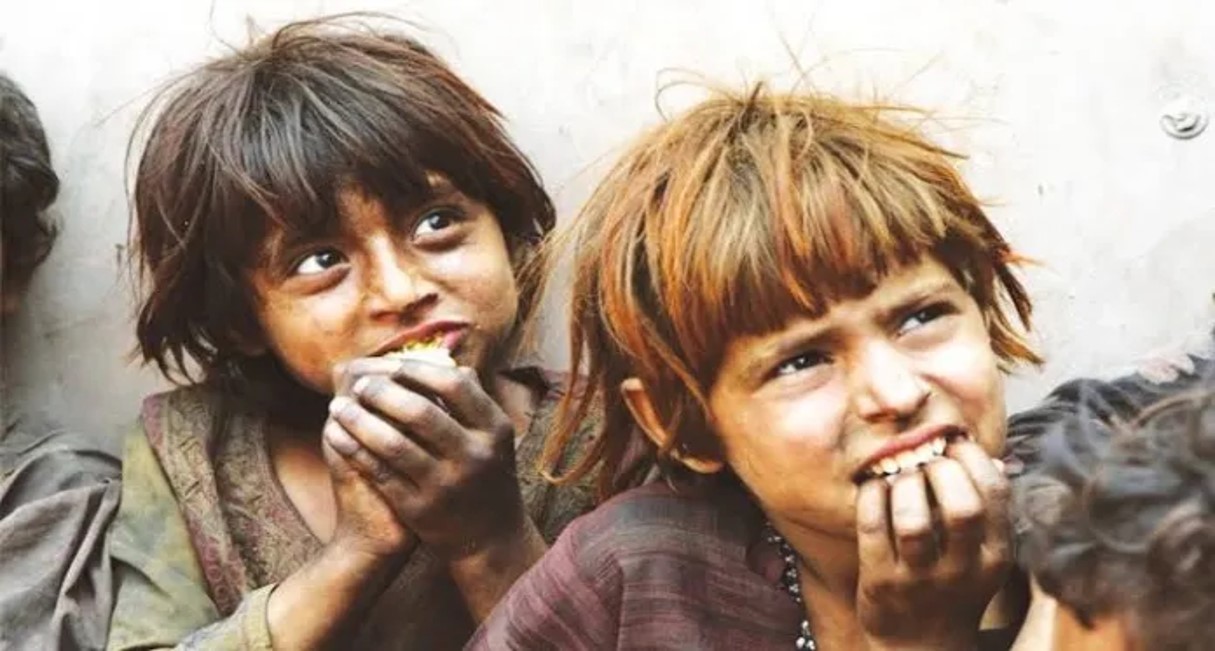

During 20 years of war in Afghanistan, according to the US-based Watson Institute’s Costs of War Project, about 176,000 people were killed, of whom 46,000 were civilians. Dreadful though they are, these figures are dwarfed by predictions by the World Health Organization that 1 million Afghan children under five will die of starvation this winter. Another 2.2 million will suffer acute malnutrition – unless urgent action is taken.

Relief organisations have warned for months of an impending humanitarian catastrophe. Now the catastrophe has arrived. “Hunger in the country has reached truly unprecedented levels,” the UN refugee agency said on 3 December. “Nearly 23 million people – that is 55% of the population – are facing extreme levels of hunger and nearly 9 million of them are at risk of famine.”

If the international community, and especially the US and Britain, which abandoned the country in August, is to prevent, or even mitigate, this coming disaster, it must act now. Some emergency aid has been supplied since the Taliban took power in Kabul, but nowhere near enough. A Marshall Plan for Afghanistan is required.

Many crises are converging. The war and its aftermath have left 3.5 million people displaced. They are particularly vulnerable. Foreign assistance, amounting to 75% of all public spending, has halted. Teachers, health professionals and civil servants have not been paid for months. As Covid rages, a drought has caused harvests to fail.

While Taliban commanders direct scant resources towards feeding and paying their fighters, the economy has seized up. The banking system is breaking down, cash and savings are hard to access, prices are rising. Per capita annual income is forecast to drop next year from $509 (£380) to $350 (£260). These are starvation wages. Meanwhile, the US Treasury and IMF have frozen $9.5bn of Afghan assets.

According to the Costs of War Project, the US has spent $2.3tn in Afghanistan since 2001. Yet direct and indirect gains, such as healthcare provision, schooling for girls and integration of women into the workforce, are being squandered, mainly due to the Taliban’s feudal attitudes but also for lack of continued western support. This self-defeating regression threatens to rebound on the west. Analysts suggest Europe could face a huge new refugee crisis next spring. Last week, 15 EU states agreed to take in 40,000 Afghans. This is welcome, but it’s a drop in the ocean. Wealthy countries, and Priti Patel’s flailing Home Office, must do more, better, quickly.

The main reasons for western governments’ reluctance to step back in – fear of validating Taliban rule and misuse of donor funds – remain valid. Yet given the urgency of the crisis, ways around this political roadblock must be found. Proposed measures to ease UN sanctions, waivers for relief agencies, cash transfers via private banks and the unfreezing of individuals’ assets should be pursued. A longer-term international assistance strategy must be formulated.

In Britain, much attention remains focused on August’s evacuation debacle. Concerns about the Foreign Office’s failure to adequately respond to Afghans’ emailed pleas for help, first reported in the Observer, and the negligent performance of then foreign secretary, Dominic Raab, have been compounded by a whistleblower’s revelations painting a picture of endemic incompetence. Raphael Marshall, who has since resigned his Foreign Office job, confirmed the impression that Raab was out of his depth. It’s surprising and disappointing that he is still in government and it’s dismaying that his successor, Liz Truss, appears to be as much interested in advancing her Tory leadership ambitions as she is in helping Afghans.

By invading Afghanistan, Britain and the US began a fight they could not finish. By leaving in a panic, they precipitated another disaster. If they are to prevent a third catastrophe, as they should, they must hurry to the aid of the starving Afghan people – immediately, generously and without further prevarication.

Courtesy: The Guardian